The Command

This poem, inspired by a visit to the site of the 1919 massacre in Amritsar, and also referencing the Troubles in Northern Ireland, Peterloo and Tienanmen Square, and with an epigram from Rwanda, is in my collection Guerrilla Country (Flight of the Dragonfly, 2024).

The command

‘An order is heavier than a stone.’

The magistrate, for fear

his fear will come to pass,

sends formal notes to regiments.

The chief of police, sure they

wish bloodshed over peace,

calls out the words that make it so.

The soldier puts in play his plan

to teach these people

what he understands.

***

A simple mark,

a sound or gesture

sets in motion—everything.

Block exit gates with bayonets.

Cut through the crowd.

Fire tear gas, baton, then live rounds

above their heads—

then lower. Aim at where

the densest groupings are.

Don’t shrink—redouble your resolve

when they begin to flee.

Send in the tanks.

***

Inside,

the image of the golden sanctum

barely shimmers,

pilgrims walk in silent circles,

heel to toe, around

the sarovar.

***

How certain must they be,

who utter these commands,

the stage they stand upon

and laud and idolise

is crumbling in the sea?

Where do their shadows go?

And where do ours,

who fail to prevent

their words?

After the forest fire

After the forest fire

Because we were four

and I only had strength to carry one

and knew no other way

I carried the one who called out loudest;

threatened us most.

You two were left to walk behind

in the dust of hot, dry summer and

the heavy mud of winter and spring.

Perhaps I thought you’d learn the land –

more likely, I just hoped we’d be OK.

That morning found us silent, slumped

among the charred remains of trees.

The flames, too, were spent after such a night.

But the undersoil still burned, untraceably,

towards where uncharred trees remained.

Social engineering

Social engineering

For desert dunes it’s 34°,

but 44 for sand dunes in the rain;

and 45 for sulphur, dynamite,

asbestos, rubble, ash, quicklime or bones;

a range from 32 to 43

for mining spoil, and 38° for snow.

At steeper angles, slopes begin to slide

as shape and gravity and time combine

with unforeseen to turn a trickle into

slump, collapse or avalanche. So mind,

for all you touch or near, the need to know—

and not exceed—their angles of repose.

————

Note: The angle of repose is the steepest angle relative to the horizontal plane at which granular material can be piled without slumping. At this angle, the material on the slope is on the verge of sliding. Any steeper, and it will collapse. The angle of repose differs between materials, for example it is 25-30° for gravel, 38° for snow, 34° for dry sand and 44° for wet sand.

“When loose particles are tipped from above, as they are in a crane-tip or a child’s sandcastle, they come to rest in a regular conical shape. The angle at the base of the cone (the angle of repose) varies with the composition of the material. In the case of the material forming the tip at Aberfan this angle was about 35°-37° to the horizontal. When the particles are dry or only slightly moist they do not stick together, as even children building sand-castles soon learn. If the material is wet — but not too wet — the particles will stick together and may stand up at an angle of repose greater than that taken up by dry material; if the material is very wet the angle of repose will be reduced, and perhaps greatly reduced. This is because the space between the particles is filled with water. This water is under pressure which varies with the height of the heap and the volume of water within it. The effect of the presence of this water is to reduce the dead weight of the heap downwards and this also reduces the resistance to lateral movement. Water is almost incompressible and if it cannot escape from the heap it acts much as a hydraulic jack in tending to lift the heap upwards. When the heap is on a deep slope the effect of gravity is to pull the heap not only downwards but also sideways. If the material starts to move on a slope it will continue downwards with less friction than normal, becoming almost fluid. The effect of adding very fine grained material (such as “tailings”) to a heap is to permit the material, when dry, to stand at an angle of repose greater than normal. But if additional water is added, whether from above by rainfall or from below by a spring or watercourse, there will be a collapse, just as a sandcastle collapses when a child empties its bucket of water on it.”

Welsh Office, 1967: Report of the Tribunal appointed to inquire into the Disaster at Aberfan on October 21st, 1966.

Shifting the rubble

Here’s another poem, Shifting the rubble, from my recent poetry collection Guerrilla Country, available from the publisher Flight of the Dragonfly Press.

Were we to blame? To know, we’d have had

to go back to before it all began.

But everything was broken. We

were victims now — hungry and cold;

and scavengers, each finding warmth

and sustenance whereby we could;

unable to name who’d made us do______.

nor find the words for what we’d done.

Instead, we piled broken stones

and bricks where shops and homes had stood,

lit fires with beams and window frames,

swept clean the littered, pitted roads;

then formed an endless chain we handed

debris, piece by piece, along

unbid, returning every brick

and stone to the pile we’d picked it from.

We paused, subdued, as convoys passed,

then walked the streets we’d cleared — and walked

before — and stood to regard the ruins,

soaring, quiet; beautiful

in evening light: cathedral windows

opening the sight of sky

to sky; fragile memorials

to_______;

and wished them to subside.

Guerrilla country

The title poem from my recent poetry collection. (Available from Flight of the Dragonfly Press.)

Guerrilla country

You climb the final rise, and reach the ridge.

A winter sunlight catches ribs and hollows

rippling out across a world that’s green—

and bleached where pain has washed the land in waves.

Touch hands with those who made these marks with stones

or picks or ploughs; with fighters, fearful how

their day would end; and those who made a mark

by ending here—in traces we can’t see.

The ground’s as new as its most recent rain,

or wind that last blew soil grain on grain;

and old as stifled cries of children hidden

in folds, or homes on hilltops, built and burned.

Be still, and listen where the quieter traces

too, of play and laughter can be heard.

Nature, nurture…

Here’s another poem from my recently published collection, Guerrilla Country. The poems in the collection explore various aspects of peace and conflict, linked to events in around 40 contexts, past and present.

The book is available from Flight of the Dragonfly Press.

Dereliction

Here’s a poem from my recent collection Guerrilla Country, available from Flight of the Dragonfly Press.

Dereliction

We learned the forest

long before we learned our books:

heard woodlarks, cuckoos, jays,

watched roebucks, martens, wolves,

each in its place and in our secret places—

hillsides, hilltops, streams and dips.

We learned that trees brought down

become a space for sunlight,

seedlings, tillers, scents and sounds;

that canopies of beech and oak

and angled beams of dancing light

make way for vistas, brambles, willow,

birch, then beech and oak

and angled beams of dancing light;

that a loved and loving land

is always moving tirelessly

from sun and sound to quiet shade,

from quiet shade to sun and sound.

Our land’s become a hungry, dull-eyed fox

made ragged and thin by mange

and hunched in the edges

hearing and seeing nothing;

limping to nowhere,

too tired to be afraid or unafraid.

Guerrilla Country – My New Poetry Collection

Guerrilla Country – my new poetry collection – out today

I’m very happy to say that my third poetry collection Guerrilla Country is published today, and can be purchased from the publishers Flight of the Dragonfly Press. The poems explore the relationship between peace, conflict and place. The book is dedicated to current and past staff and collaborators of peacebuilding organisation International Alert, whose Executive Director Nic Hailey has kindly written an introduction.

The book’s stunning cover is based on a photograph by Jonathan Banks. Jonathan kindly allowed us to use his picture of a dancer at the Peace and Culture Festival organised by International Alert in Liberia in 2008, celebrating Unity in Diversity as part of Liberia’s post-conflict recovery.

I worked for International Alert for more than a decade, and other NGOs before that. Guerrilla Country is partly my personal response to witnessing and trying to understand how conflict evolves into peace and how this process can be helped; as well as how fragile or seemingly stable situations so often revert or degenerate into violence.

The poems reflect on events in almost 40 different contexts, past and present, from Texas to Rwanda, via Afghanistan, Amristar, Belfast, Ukraine, Runnymede and Peterloo. I’m hoping the poems will be of interest, not just to the usual poetry audience, but also those involved in peacebuilding.

Here’s a small taste:

The King's Peace

To keep his peace, our king built temples,

courts and palaces, and scarred

the land he'd won, with ditches, ports

and roads; determined how we die;

and blessed us with his enmities.

To teach us irony, he named

his cousins lords and justices.

Apprised of God's mistake by priests

and clerks, on pain of punishment

he made us speak a single tongue.

His word was written, maps were drawn.

But laws and maps and roadways lengthened

distances, and when he sailed,

he left no instrument through which

to see, but a kaleidoscope.

We turn and turn its wheels, but cannot

make the fractured picture whole.

Choosing the score

They sought a music to

replace D major,

kettledrums and brass;

a music ending on

a quiet, sustained

C major tutti chord.

But the scores they chose

were beyond their grasp

or opened a hidden door.

Comments on the book by other poets

Raine Geoghegan

These are stirring poems with strong themes of war, hardship, freedom and renewal. Vernon writes from the perspective of both witness and peacebuilder. He illustrates the many complexities of war and conflict and through this lens the reader begins to glimpse both the harshness of war but also the beauty of peace. His observations are clear, concise and they take us on a road which he has clearly travelled. The poet and the peacebuilder are present in each poem. From the powerful imagery in The AK47 – my perfect design, ‘I run towards the gunfire, but/ I have no gun to love and hold’, to the poignant words in Aminata’s song, ‘My brothers, we challenge you now/ to gather your cousins and friends/ know how to stand your ground/ and when and how to bend.’ This is a brilliant collection. Go buy a copy.

Jack Caradoc

Guerilla Country is a far-reaching book in scope and complexity. A record, a journal of humanity in conflict. Vernon’s poetically sharp eye presents the terrible actualities both historically and in the political present, inviting us to consider often horror in our world but also the vital need for hope in the face of it. The light of poetry illuminating the darkest places as it should. Powerful words.

Susan Wicks

Guerrilla Country is a courageous book, with poems inspired by a wide geography of contemporary and historical battles – all the braver for its structure, which juxtaposes distant unnamed scenarios of conflict with some of the landscapes of deprivation that must have made them inevitable. We glimpse the forms and colours of medieval pageantry, and its aftermath. We see the patterns Kitchener left in the sand at Khartoum. And we hear Aminata’s song of stolen herds and hunger in a home with ‘no okra sauce’. Follow the clues to find yourself in a place of huge empathy, where war may be the shared language but measured thought and humanity still prevail.

Jess Mookherjee

The reader of Phil Vernon’s carefully wrought poems of witness in Guerrilla Country will meet displaced people and danger, and will run into gunfire. And yet nature persists, and through the passage of time and verse we also meet a kind of peace.

Reclamation

Reclamation

I. Tea Plantation

The pickers have long fled south, to bivouacs

that drip with cold; the geometry of tea

subverted where muhuti and flame trees

break cover, watching over weeds and vines.

Hyrax scurry from their burrows. Leopards

have returned to where they never knew.

Cranes circle high above the miracle

of sunbirds drawing nectar, motionless,

from coral and jewels they’d never have found before.

Black kites regard the rebel bands in tired

fatigues and rubber shoes, who thread their quiet

patrols on paths they’ve reimposed on the faintest

traces of a matrix overgrown.

II. Seat of power

And far away, where warlords feasted long

ago, and made their will known to the men

they charged to make it so—and where a king

was killed—the broken masonry is mocked

by oak and birch. A cenotaph’s obscured

by briars among which feral goats and cattle

browse—and dogs in sunken doorways wait

in ambush to reduce those herds to blood

and bones they’ll bare their teeth and battle for.

The dogs are watched in turn from shadowed vantage

points by scouts who’ve travelled from their sundered

homes across a narrow, hostile sea

in search of knowledge of what happened here,

to send back to their camps among the dunes.

This poem was included in Kent & Sussex Folio #76 in 2022. It is part of what I hope will be published as a new collection, of poems exploring the interactions between conflict, peace and place: Guerrilla Country.

(The Muhuti tree is Erythrina abysynica)

The UN and other parts of the international aid system are re-emphasising their important peacebuilding role. This matters, as peacebuilding is needed more than ever, and it can’t be left to specialist peacebuilders alone. But the process risks being stymied by a lack of clarity about what ‘peace’ looks like in practice, and therefore how to get there. In this article I propose a simple, generic and adaptable solution.

An increased emphasis on peacebuilding

There has been a welcome resurgence of emphasis in the peacebuilding mission of the United Nations and its Member States and Organisations, over recent years. This commitment has been reflected in UN and Member State policies such as Sustaining Peace and Pathways for Peace, which define an overarching commitment to building peace in line with SDG16, and more broadly across the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs). These are supported by specific policies such as UN Security Council Resolution (UNSCR) 2250 on Youth Peace and Security (YPS), the longstanding Women Peace and Security (WPS) agenda, and by individual Member State commitments.

Many technical UN organisations have formally adopted peacebuilding within or alongside their core strategies. Donor agencies increasingly require programmes to be designed with an awareness of conflict dynamics, and contribute to peace (i.e. be ‘conflict sensitive’). The International Financial Institutions have also adopted policies for conflict-affected settings, such as the Fragility, Conflict and Violence Strategy of the World Bank Group and the International Monetary Fund’s Strategy for Fragile and Conflict-Affected Countries. The aid community has committed to implementing the Humanitarian, Development and Peace Nexus (HDPN), designed to minimise silos and help programmes succeed in fluid and evolving situations.

All this matters, because the number and intensity of conflicts across the world has been on the rise for some time; because geopolitics has become less stable on a macro scale; because far too many people carry grievances about being unfairly excluded from the benefits of development; and because of the security implications of environmental degradation, among other stresses. It also matters because sustainable peace needs all hands to the pump, rather than being left only to peace specialists, who are too few in number and are under-resourced. Hence it’s important that UN and other agencies contribute significantly to building peace.

Progress?

It is early days yet, and perhaps too early to expect to see significant evidence of the impact of these changes, whether locally, nationally or regionally. Nevertheless, concerns have been raised within the peacebuilding community about whether this widespread adoption of the language of peacebuilding is leading to a genuine change in the way these organisations do business. Some commentators have suggested that, beneath the new rhetorical dressing, most organisations are in fact continuing with business as usual. In other words, adopting the uniform of peacebuilding, but not its practice. This is partly about the need to provide more funds and in new ways. It is also about the difficulty of converting agencies which have evolved to perform specific tasks, to adapt their technical and cultural approaches so as to embrace peacebuilding. This will only happen if the challenges to change are addressed in terms of individual motivation, knowledge and skills, new organisational strategies, effective leadership, and a more conducive organisational and sectoral environment.

Progress can of course be tested by looking at what activities are being carried out, and whether or not they differ substantially from what the agencies were doing before. Because the adoption of peacebuilding clearly requires a visible and substantive change in the way they work. This is because peacebuilding actions are designed to achieve recognisably different ends than ‘development’ or ‘humanitarian’ actions. For example, a developmental education project might focus on improving sustained education outcomes for girls; a humanitarian education project might focus on providing continuity of education services to internally displaced children; whereas a peacebuilding approach to education would be designed specifically to address either the identified causes of conflict, and/or to contribute to an agreed understanding of how peace might be sustained. Obviously it would be designed specifically for the context. But to take an example, one might expect to see an education programme in a conflict-affected context designed to increase education attendance and outcomes among marginalised communities, where their marginalisation has been identified as one of the causes of conflict. And it might also emphasise the involvement of parents and other community members in school management, as a way to improve their sense of empowerment and ownership, since these qualities are often seen as critical to sustaining peace.

Peace: a broad church, yes, but is it too vague?

One of the curious features of the adoption of peacebuilding among UN and other institutions is that they all-too-frequently fail to declare adequately what they mean by ‘peace’. In a context where many staff and other stakeholders of these organisations may be unclear what they are newly being asked to do, this can be a problem. It means they don’t have a clear understanding of what’s required of them, and in the absence of such, many will be tempted to carry on with what they do know and understand: in other words, business as usual. At a very practical level, this lack of clarity also creates a problem for accountability and monitoring and evaluation (M&E): if we haven’t agreed on what we are aiming for, how can we be held to account for making progress towards it?

This is doubly problematic because ‘peace’ is a fairly vague concept for many; and where they do apply a more specific definition, it can be incomplete, or even in some cases downright unhelpful. Often, peace is seen simply as equating to bringing violence to an end and restoring stability. But this misses the important element of ‘positive peace’—i.e. the sustained presence of factors, behaviours and institutions within and between societies that prevent further outbreaks of violence and enable effective co-existence. After all, half of all armed conflicts between 1989 and 2018 recurred, and one in five recurred three or more times. Mere stability—important though it is—often masks the persistence of grievances and other problems that risk creating further conflicts in the future. For the UN and other major multilaterals meanwhile, peace is often written about in terms of ‘conflict prevention’ or ‘post-conflict recovery’, and this terminology can also draw attention away from the need to promote positive and sustainable peace. Worse, for all too many actors, ‘peace’ is defined in terms of their own victory over others, or of maintaining a status quo from which they and their constituents benefit disproportionately, at the expense of others.

Towards an agreed definition of Peace

Of course, peace is not just a technical issue. On the contrary, it is highly political and therefore highly contextual. This can make it hard to strive for definitions that combine integrity and clarity, because some people or groups may have good reason to shy away from an objective and accurate narrative, especially if it threatens their interests as they perceive them. This is why peace making and peacebuilding are so often approached through a lens of ‘strategic ambiguity’. It is true that this approach can create the kind of ‘big tent’ that peacebuilding so often requires, bringing together different interest groups under a single banner, and seeking the kinds of compromises needed to avoid violence or bring it to a close. But this can be confusing for those not closely involved at the political level. For the staff of organisations tasked with making a contribution to peace in their programmes, it can make it hard to see clearly what is needed. This means it is all the more essential for organisations to own a simple and clear understanding—internally at least—of what kinds of things they should aim to support when they say they are building peace. With this in mind, I propose a broad, generic definition. This draws on manifold sources but has its roots in the concepts of peacebuilding we developed more than a decade ago when I worked for International Alert:

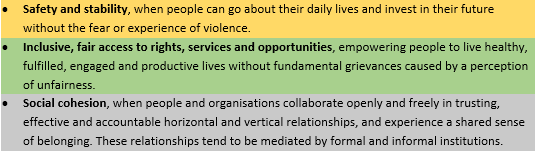

Peace is when societies are anticipating, managing or resolving conflicts non-violently, while continuing to meet peoples’ basic needs and make development progress. In practical terms, their capacity to do so can be seen as the product of three broad, interlinked and overlapping factors: the three core dimensions of peace, if you will. These reflect both the impact of peace on people and their communities/societies, but also their own active engagement in sustaining peace (which is essential, for peace requires constant nourishment from within):

NB: ‘vertical and horizontal relationships’ refer to two-way interactions and relationships between people and those in authority, and between and among people and peoples.

This concept has several advantages.

- It is simple: easy to understand.

- It incorporates fairness: something people tend to understand far more readily than technical concepts such as ‘inclusion’, ‘marginalisation’ or ‘equity’. (And fairness is a more realistic and achievable criterion than ‘equality’.) Sustainable peace requires that safety, stability and access to opportunity are all fairly available, and the institutions that govern and enable social cohesion should also promote fairness.

- The concept encapsulates not just negative peace (i.e. reduced violence) but also positive peace (the construction and strengthening of habits that allow for non-violent problem resolution, and the institutions that support these.)

- It can be applied at any scale, from village or suburb to regional or even global geopolitics.

- It acknowledges the interaction between its three elements. Improved safety and stability create an environment conducive to improving access to opportunity and to the development of mechanisms that enhance social cohesion. Enhanced opportunities enable people to take part in these social cohesion mechanisms, and they reduce the grievances that might otherwise threaten stability and security. And social cohesion breeds trust and allows for mechanisms that improve security and provide fairer access to opportunities. A virtuous circle.

Measuring progress towards peace

This simple concept of peace can also be integrated readily with humanitarian or developmental activities, so it’s helpful in promoting the HDP Nexus, and allows agencies historically focused on humanitarian or development to adopt practical peacebuilding measures. For example, the Food and Agriculture Organisation (FAO) can easily build social cohesion and fair access goals into its work on land management, in places where access to and use of land are sources of conflict (as is so often the case). Or the UN Population Fund (UNFPA) might help young people steer away from violently criminal or extremist pathways, alongside its existing work on young people’s sexual health. One reason this concept of peace readily enables this kind of integration is because, while its goals are reasonably clear, it is resolutely non-prescriptive regarding strategy, i.e. how to reach those goals. Thus it allows plenty of room for creative programming, linked to any number of technical development or humanitarian priorities.

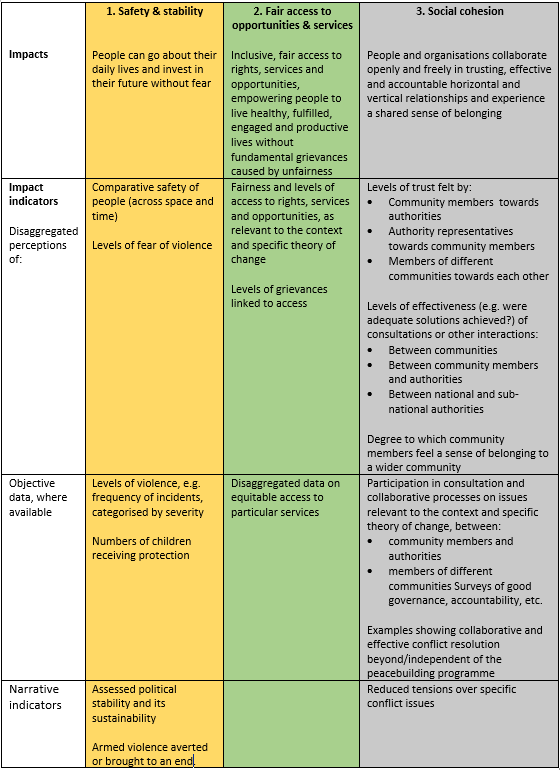

This means that M&E can focus on a few core, consistent top level indicators, while developing context- and programme-specific indicators at output and even outcome level. For example, one might envisage goal indicators along the lines suggested in the table below.

This M&E model uses a combination of objectively verifiable indicators (levels of violence, levels of participation, and so on); surveys of people’s perceptions – since perceptions are so vital to stability and fairness – and thus grievances; and what we might call ‘narrative indicators’, e.g. reports of violence averted, or conflict issues resolved.

It’s also worth noting that the indicators proposed here are designed to be scalable, i.e. they can be adapted and measured locally, nationally or even internationally.

In the following table, each of the three core components of peace are considered separately. In practice, as noted above, there is considerable overlap and interaction between them, which can be taken into account in devising theories of change and M&E elements in actual peacebuilding contexts.

Conclusions

These ideas are intentionally simple. They have their limits. But at least they are clear. As such they, or something similar, could be used as the basis for developing a clear definition of peace, so that agencies adopting peacebuilding can explain both internally and externally what this means. This would give their staff a solid basis on which to develop creative programming approaches, to measure progress, and to be held accountable by others.